Painting of a girl with dolls. Photo by National Library of Russia on Unsplash.

Contents

- What is a doll?

- Multi-materiality of dolls

- A brief note on storage, display and repair

- The "true nature" of a doll

- Dolls as sources of historical information

- Dolls as objects with particular social identities

- Conclusions

- Acknowledgments

- Bibliography

What is a doll?

Before even beginning to be able to talk about doll conservation, we run into a very basic question: what should count as a doll and what shouldn’t? Are dolls simply toys? Or are they objects of ritual and ceremony such as voodoo ‘dolls’ (Clar 1959), Katcina dolls (Teiwes 1991) and small statues of Christian characters such as the Virgin Mary? Do automatons count as dolls or machines (Brooks et al. 2007:253)? Do the French fashion dolls of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that were used to display wealth and finery but not for play (Dixon 1990:65) count as dolls? Should any anthropomorphised figurine count as a doll? Where do we draw the boundaries for them?

For the purpose of this article, and to narrow down the scope of what I mean, I will use the online Merriam Webster’s definition of a doll: “a small-scale figure of a human being used especially as a child's plaything” (Merriam-Webster online).

With this definition in mind, I will address the main technical problems for their conservation arising from the multi-materiality of dolls given their historical-social origins and development.

I will take a brief look at the ethical issues for the conservation of dolls, given that people – especially previous owners – will have very specific expectations of what should be done with their ‘old friends’ and childhood companions. Dolls are proof that conservation ethics are inseparable from what objects mean to us.

Multi-materiality of dolls

Given the enormous range of materials that have been used in doll making (whether home-crafted, as a small cottage industry or full industrial production) all around the world, and the increasingly complicated dolls made today that wet themselves, talk and move with increasingly uncanny resemblance to real humans, it would be impossible to go into fine detail regarding the technical conservation of all aspects of them. However, some examples will be given regarding the types of materials that may be seen, the most common problems found in doll collections today and how they are overcome.

A (very) brief and generalised historical overview of dolls would show a shift in materials as the process became less home-centred and more industrialised. It is not uncommon to find very old dolls made of straw, cornhusk, dried apples (Eaton 1985:15), animal bones (Gardner 2013), nuts of various kinds for the heads (Chambers 2013) and rags.

Faceless Amish dolls from the Smithsonian American Art Museum and its Renwick Gallery. 1940s. Object # 2016.57.11.

Dolls with moving eyes appeared in England around 1825 (Dixon 1990:50-51), and by the mid-nineteenth century, poorer-class dolls has painted eyes and hair while the upper-class dolls had glass eyes and attached hair (Dixon 1990:50-51).

When bisque dolls began to be made, the porcelain heads and arms were being mass produced in the same factories together with the plates and saucers and were only later combined with the rest of the body in a separate production process altogether (Brooks et al. 2007:251-252; Caruso 1999:5).

In America, early dolls were made of ‘secret formulas’ that were manufacturer-specific and combined varying amounts of sawdust, glue, bran, plaster of Paris (Gaylin 1976:28), wood pulp, rags, scraps of leather and even ground-up bone (Brooks et al. 2007:251).

Thus, before the arrival of modern plastics and polymers, almost anything from leather to metal to hair to wax to textiles could be found on a doll. In fact, there were so many mixtures for doll bodies, that the term “composition” doll today is used to mean “any dollmaking substance that is not obviously wax, wood, metal, ceramic, paper, etc.” (Eaton 1985:33).

Apple-head doll. Photo by Mich3451 via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Paper Doll Costume, White Veiled Dress from the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. 1876–80. Object # 1937-22-14.

The following table is an example of the number of materials that may be found in a single doll (Storch n/d:2):

| Body part | Materials |

|---|---|

| Hair | Dyed mohair (sheep), human hair, boar bristles for eyelashes |

| Shoes | Tanned leather |

| Cape | Wool |

| Fastener | Steel |

| Dress | Cotton |

| Underwear | Dyed nylon, cotton |

| Accessories | Plastics, ink, enamel, paper |

| Skin | Shellac |

| Eyes | Glass |

| Mechanisms | Steel, rubber bands, lead, cork |

Because of the particular dolls he was working on, Storch does not encounter the presence of silks, furs, wax, and modern polymers, but these can also be easily found in dolls today.

Additionally, Faith Eaton describes dolls made of natural materials such as straw, raffia, flax, palm fibres and fur (Eaton 1985:73). There are also edible dolls made of chocolate, sugar, bread, marzipan and prunes (Eaton 1985:42).

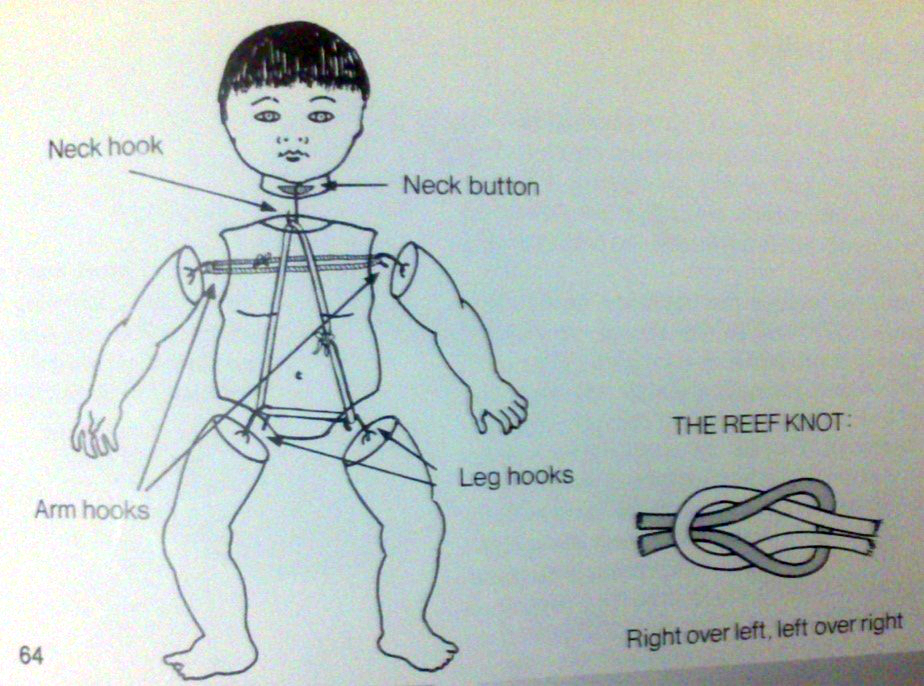

Thus, it becomes clear that doll conservation must be approached from the multiplicity of the materials found in each specimen. This is evidenced by Mary Caruso’s division of her book on doll repair into specific sections such as ‘eye repair’ (Caruso 1999:65-88), ‘wig care’ (Caruso 1999:89-112), and ‘dressing and costume care’ (Caruso 1999:113-140). Faith Eaton does similarly by devoting specific sections in her book to rubber dolls (Eaton 1985:91), wax dolls (Eaton 1985:111-113), leather (Eaton 1985:64-66) and paper (Eaton 1985:79-81) among others. Special attention is also given to the importance of restringing and rewiring dolls whose inner rubber bands and metal attachments have deteriorated causing dismemberment (Eaton 1985:12-14).

Diagram showing how a doll is supposed to be restrung. (Perry 1985:71)

A brief note on storage, display and repair

Due to the many elements of both cellulosic and proteic origin found in dolls, one of the problems reported in doll collections are insects: moths, vodka beetles and carpet beetle larvae, among others (Gardner 2013; Lutman 2013). Little can be done about them but to employ a proper Integrated Pest Management plan (Pinninger & Wilson 2011).

The second biggest problems involve fading due to light and decaying plastics. Very little can be done about these as well other than controlling the light levels based on each individual case (Michalski 2011) and controlling the temperature around the dolls.

A compromise must be struck between the dolls’ display and conservation (Keene 1994:19; Butler & Davis 2006:7). For storage, dolls are padded with polyethylene foam, small pillows of unbleached muslin under the doll’s faces (Storch n/d:5), and they are laid face down to prevent the mechanisms for moving eyes from causing pressures inside the dolls’ heads and falling away (Eaton 1985:14).

Dolls facing down during storage (Storch n/d:7)

One of the further problems with dolls and their varied compositions, as Brooks et al. have pointed out, is that sometimes they cannot be physically taken apart (Brooks et al. 2007:256) neither for examination or conservation purposes because they have been created stitched or glued together – good reasons for X-radiographing them.

In these cases, treatment must be even more careful, taking care of not damaging one material while trying to get to another. It may even have to be decided that it is not worth the risk trying to stabilise one material at the risk of another – how to choose which one material on the doll is more important? Is it a consistent conservation decision to make such choices on the same object? These questions bring us to the ethical side of doll conservation.

The "true nature" of a doll

“One doll came in that was really about gone. The cloth body had been torn and patched. Its hair was almost gone and very soiled. In a few days, all dressed in new garments, she looked like new again. The little owner came with her mother to get it, but somehow she just held her hands behind her, and didn’t even want to touch it. In moving it, the doll cried “Mama” and then the little girl recognized her doll, reached out quickly with just a trace of tears, hugged her doll and was happy.” (Gaylin 1976:68)

Before beginning any conservation treatment, we must understand the object in question. Dolls are a particular case: because they are anthropomorphic by nature, we react to them; and because the dolls I’m referring to in this article have at some point or another very likely belonged to children – these are objects that have shaped identities (Sutton-Smith 1986:242).

According to Bailey, children use dolls in an act of “scaled perception” to position themselves in the world and understand hierarchies of power (Bailey 2005:68). Dolls, through the way they are made to look by their producers, present to children social conventions, sexual representations, and behavioural expectations which help them build a picture of their expected place in society (Bailey 2005:70, 73, 84).

Superman action figure. Check out all those action joints! Photo by King Lip on Unsplash.

For example, an Action Man is a fully-jointed doll meant to be able to take many different active positions. It has been moulded with toned musculature and large hands capable of gripping its various weapon accessories. Some models have moving eyes to allow the doll to look ‘alert’ (Dixon 1990:122-123). The impression of such a build is that this doll is meant to engage actively. This toy has been made for action play, therefore, the child must use it for action play – it makes no sense to sit Action Man down for tea – something that makes perfect sense for the stiff-limbed Barbies™ and other dolls directed at young girls (Dixon 1990). I was about to complain that Barbies™ don't even have knee joints in order to sit them down properly for tea... but apparently new Barbies do. How... progressive... I'll not go into the gender implications imbued into doll construction, but they can be quite glaring.

Similarly, the noises and smells some ‘baby dolls’ have demand certain types of attention from their ‘mothering’ little girls (Dixon 1990:16). As such, these details are of integral importance to a particular doll’s identity. Having a minimally-conserved Action Man with atrophied joints or, on the other hand, leaving a baby-doll with a non-working crying mechanism inside because it is difficult to get to could, in fact, be hurting the readability of the artefact. They would be losing an important part of their original nature and purpose.

Dolls as sources of historical information

“Unlike documentary sources – so often written by ‘winners’ (and those other ‘dead white men’ who shaped the sources of academic history as it was studied in the nineteenth century) – material survivals could ‘speak’ of those in the past who had little or no textual ‘voice’.” (Pennell 2010:174)

“Artefacts are important because they can be used as evidence of something that was part of the past” (Riello 2010:25). Damage on a doll is like a wear-mark on a tool. Lack of hair, pen marks, soiling are all proof of ‘a child’s love’.

Similarly, hairstyles changed rapidly in the 19th century, and doll makers often tried to make their dolls appear fashionably up-to-date (Hogan 2010) – the smallest alteration to a doll’s hairdo would create a historical anachronism. The conservator would be reshaping history.

Furthermore, when thinking about conserving or restoring the costume on a doll, it must be kept in mind that the last person who dressed that doll may have been a very important one – or perhaps it was a child interpreting how women’s clothes were meant to be worn in their time – and thus the way that the doll was dressed should remain as evidence of that person’s hand (Mary Brooks, personal communication).

Following what Pennell said, any changes made to a doll would effectively erase that ‘voice’ of the object and its last owners and replace it with the conservator’s interpretation. Since “objects should not be used as an aid for providing enhanced answers, but for asking better questions” (Riello 2010:29), it would be important to weigh the benefits of conservation against the possible loss of history that could result from doll handling.

Dolls as objects with particular social identities

“An elderly lady brought in an antique doll in very bad shape; she had a tintype picture of the doll held by her mother when she was only eight years old. The customer said that she had never seen the doll all together, but had kept it in a box all these years. The doll was restored to better than new, and clothes made just like the ones in the picture. When the owner came to pick up the doll, she was so happy about it that she could hardly speak.” (Gaylin 1976:26)

If our objects are the results of human production, would it not make sense for them to always remain in human use? The above quote from one of Gaylin’s doll hospital anecdotes echoes with sentimentality and the dynamics of human memory, emotion, and the ways in which we link material objects with affections.

Should professional conservators be the ever-striving scholars looking for the preservation of historical evidence?

Would it be too outrageous to consider the possibility of conserving and restoring for the sake of our feelings, our characteristic human nostalgia, regardless of the chances of inaccuracy in recreation and the loss of material information?

After all, doesn’t that elderly lady’s happiness make it worth it?

Why else would we be conserving objects otherwise – to save knowledge for the sake of knowledge?

I cannot answer these questions directly. However, this aspect of restoration must be taken into account before embarking on the conservation of an object such as a doll – not just any object, but an anthropomorphised figure who was once someone’s friend and companion.

Portrait of girl with doll: Portret van een kind met een pop, anonymous, c. 1883 - 1886. Rijksmuseum collection. France. Object # RP-F-2007-66-59-5

Conclusions

“I love old dolls, not for their perfection or for the amount of money they may bring, but for the grace of a bygone era, for their lifelike charm, and for the love that was once given to them… I look at dolls with a loving eye; if I can rescue that gem for posterity, flawless or not, I will. How can we allow such treasures to disappear?” (Koval 1992:7)

“Museums collect these emotive artefacts both to record important aspects of personal and social histories and also to understand their manufacture and materials” (Brooks et al. 2007:249). Dolls are preserved “for future generations of visitors to see and enjoy and to provide information about children’s lives in the past” (Gardner 2013).

So, should we consider dolls as personal pasts or authoritative pasts? Are they heirlooms or sources of information? (Caple 2006:205) They are both, and therefore must be handled with care. As I have expressed above, conservation is very easily capable of changing the meaning of a doll (historically, socially, contextually), and thus, for each kind of doll, each particular artefact, different considerations must apply – including taking into account whether the doll belongs to a museum or a private person and what its purpose is (display, storage or use).

As France-Lanord said, “restoration means to renew not only a material but a product of human activity” (France-Lanord 1996:245), and as such, “the activity of conservation cannot therefore aim to bring back the material from which the object was made; it must instead restore the object all of its meaning as an embodiment of the imagination” (France-Lanord 1996:245). This particular view is perfectly appropriate in the case of dolls. It is essential to remember what they were made for, who they were made for, who they were owned by and how they were treated to make a better decision of what should be done to them.

Doll conservation requires the striking of a fine balance between the gung-ho attitudes of the loving ‘nurses’ at the so-called ‘doll hospitals’ (Koval 1992; Gaylin 1976; Eaton 198; Perry 1985), and the scholarly pursuits of conservators intent on the preservation of information. It would be ideal to inform doll owners of the historical importance of their little charges so that no extreme restorations take place and to remind conservators that we are not treating simple historical objects, but artefacts that have, through their being, influenced human lives and emotions.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the following people for their support and generous help with information during the writing of this essay: Dr. Chris Caple (Durham University), Dr. Mary Brooks (Durham University), Dr. Robin Skeates (Durham University), Mr. Charles Chambers (Vina’s Doll Gallery), Ms. Susan Gardner (Museum of Childhood, Edinburgh), Ms. Esther Lutman (Victoria & Albert Museum of Childhood), and Ms. Nancie Ravenel (Shelburne Museum).

If you liked this post, you can follow me on Twitter where I'll be posting more information on the conservation of various materials.

Bibliography

Bailey, D. W. (2005). Prehistoric figurines: representation and corporeality in the Neolithic. London, Routledge. p.66-87.

Brooks, M. et al. (2007) X-radiography of dolls and toys. In: Brooks, M. and O'connor, S. eds. (2007) X-radiography of textiles, dress and related objects. 1st ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, p.249-265.

Butler, C., & Davis, M. (2006). Things fall apart: museum conservation in practice. Cardiff, National Museums and Galleries of Wales.

Caruso, M. (1999). Care of favorite dolls: antique bisque conservation. Grantsville, MD, Hobby House Press.

Caple, C. (2006). Objects: reluctant witnesses to the past. London, Routledge.

Chambers, C., [email protected] (2013) Re: Doll repair. [email] Message to Isa-Adaniya, A. ([email protected]). Sent 5th March 2013.

Clar, M. (1959) Poison Voodoo Dolls. Western Folklore, 18 (No.4 (Oct. 1959)), p.337.

Dixon, B. (1990). Playing them false: a study of children's toys, games and puzzles. Stoke - on - Trent, Trentham.

Eaton, F. (1985). Care & repair of antique & modern dolls. London, B.T. Batsford.

Florian, M. (2006) The mechanisms of deterioration in leather. In: Kite, M. and Thomson, R. eds. (2006)Conservation of leather and related materials. 1st ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, p.36-57.

France-Lanord, Albert. (1996). Knowing How to “Question” the Object before Restoring It. In: Price, N.S.; Talley Jr., M.K.; Melucco Vaccaro, A. Historical and Philosophical Issues in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage. Washington: The Getty Conservation Institute. 244-247

Gardner, S., [email protected] (2013) Re: doll conservation. [email] Message to Isa-Adaniya, A. ([email protected]). Sent 6th March 2013.

Gaylin, E. (1976). Doll repair. Riverdale, Md, Hobby House Press.

Harley, C. (1993) A note on the crystal growth on the surface of a wax artefact. Studies in Conservation, 38 (No.1 (Feb. 1993)), p.63-66.

Hogan, P (2010). The Curious Case of the China Doll - National Museum of Play. [online] Available at: https://www.museumofplay.org/blog/the-curious-case-of-the-china-doll/ [Accessed: 07 Jan 2023].

Keene, S (1994). Objects as systems: A new challenge for conservation. In: Oddy, W. A. (1994). Restoration : is it acceptable? [London], British Museum Department of Conservation. p.19-26.

Koval, B. (1992). How to repair & restore dolls. Robert Hale.

Landi, S. (1985). The textile conservator's manual. London, Butterworths.

Lutman, E., [email protected] (2013) Re: Doll conservation enquiry - Masters degree. [email] Message to Isa-Adaniya, A. ([email protected]). Sent 5th March 2013.

Merriam-webster.com (n.d.) Doll - Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary. [online] Available at: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/doll [Accessed: 13 Mar 2013].

Michalski, S (2011) The Lighting Decision.In: Caple, C. eds. (2011) Preventive Conservation in Museums. 1st ed. Abingdon: Routledge, p.319-335

Murrell, V. (1971) Some aspects of the conservation of wax models. Studies in Conservation, 16 (No.3 (Aug. 1971)), p.95-109.

National Trust (Great Britain). (2011). The National Trust manual of housekeeping: care and conservation of collections in historic houses. Swindon, Wiltshire, National Trust.

Pennell, S (2010). Mundane materiality, or, should small things still be forgotten? Material culture, micro-histories and the problem of scale. In: Harvey, K. (2010). History and material culture: a student's guide to approaching alternative sources. London, Routledge.

Perry, D. (1985). Restoring dolls, a practical guide. London, Bishopsgate Press.

Pinninger, D. and Winsor, P. (2011) Integrated Pest Management. In: Caple, C. eds. (2011) Preventive Conservation in Museums. 1st ed. Abingdon: Routledge, p.169-196.

Quye, A. and Keneghan, B. (1999) Degradation. In: Quye, A. and Williamson, C. eds. (2013) Plastics: collecting and conserving. 1st ed. Edinburgh: NMS Publishing, p.111-135.

Ravenel, N., [email protected] (2013) Re: Doll conservation enquiry - Masters degree. [email] Message to Isa-Adaniya, A. ([email protected]). Sent 4th March 2013.

Riello, G (2010). Things that shape history: Material culture and historical narratives. In: Harvey, K. (2010). History and material culture: a student's guide to approaching alternative sources. London, Routledge.

Sandler, C (2011). Strong Connections - National Museum of Play. [online] Available at: https://www.museumofplay.org/blog/strong-connections/ [Accessed: 07 Jan 2023].

Storch, P. S. (n.d.) Ancker doll technical report. [online] Available at: http://www.mnhs.org/preserve/conservation/reports/anckerproject.pdf [Accessed: 12 Mar 2013].

Sutton-Smith, B. (1986). Toys as culture. New York, N.Y., Gardner Press.

Teiwes, H., & Hanna, F. (1991). Kachina dolls: the art of Hopi carvers. Tucson, University of Arizona Press.

Williams, N. (1983). Porcelain: repair and restoration. London, British Museum Publications.