Often, conservators will talk about the principle of minimum intervention and not touching up objects a lot. Sometimes, it will be argued that a restoration is absolutely necessary for the sake of the object. How do we make those decisions? When does each apply?

What can we say about restoration?

- Not restoring things may give a distorted image of the past as broken and damaged.

- Not restoring calls attention away from the object’s aesthetic appearance and towards its damage.

- Restoration is useful to explain how things worked, sounded, looked and felt.

- Restoration can be essential when we talk about working objects like musical instruments or clocks. Some objects were created to be dynamic and cannot be interpreted accurately if they stop moving.

Parisian-made gilt-bronze clock. c. 1770 - c. 1775. From the Rijksmuseum collection. See here. Is a clock still a clock if it doesn't tell the time anymore?

- Restoration is capable of showing technical, social and economic changes through time.

- Restoration involves the audience. It makes history interesting. Everyone likes to see amazing Before and After pictures.

- Restoration can increase the stability of the object.

- Modern, professional restoration ethical codes emphasize a respect for the remaining original material.

- Even bad restorations in the past helped us have things now. Many of those restorations can be redone and fixed, although not all of them.

- Restoration is about the meaning of the object, which is more valuable than the material itself. The idea is that the social functionality of the object impacts society more than its damaged appearance.

- Restoration might be the only option to save “emergency” objects affected by insect attack, floods, fires, etc.

- Restoration is affected by our perceptions of the past. Just like Victorians tearing down original historical buildings to create fake "gothic" reconstructions, we could be misinterpreting the past and restoring something inaccurately.

- Restoration is sometimes purely concerned with aesthetics. It can be more interested in making something look "new" or "good" than in respecting authenticity.

- Restoration can be used for political means. Choices on what gets or does not get restored can create "biased" histories. Restoration methods or choices can also be used to ignore or highlight different aspects of an object. The identity of the restorer can be defended or attacked based on the "identity" of the object. Certain religious items, for example, "cannot" be restored by women.

- Restoration can affect the ease of care for objects in the future. A good restoration can improve the chances of an object while a bad one can destroy it completely.

What are minimum intervention and the concept of stewardship about?

- Minimum intervention is (arguably) the minimum amount of work necessary to physically and chemically stabilise an object and prevent further degradation. This term is subjective.

- The idea of stewardship is that people of the present are only stewards of the objecs of the past (or of the present), keeping them safe for the sake of the people of the future. Thus, we are not owners, but only caretakers. This principle implies that as caretakers, not owners, we do not have the prerogative to make many decisions about the objects we care for. If you borrow an item from a friend, do you have the right to send it off to get altered?

- Restoration removes information. Many restorations require cleaning and removal of original material.

Wooden bowl from the wreck of the Dutch East Indiaman Witte Leeuw, anonymous, before 1613. From the Rijksmuseum collection. See here. Should this object be restored? Are aesthetics the most important aspect of an object? The shipwreck destruction is a part of its history.

-

The less we do to an object, the less likely we are to mess it up. Old restorations have sometimes proven to be worse for objects than leaving them be.

-

Is it culturally appropriate to restore an object? Some objects were made to be destroyed. They were meant to decay. It was a symbolic gesture. Think of grave goods. In some cases, they are supposed to degrade along with the body of the deceased. Would it be disrespectful to deny them this destiny? Some objects were ritually killed by bending or breaking them. Would it make sense to stick them back together?

-

If parts are continually replaced, what is the original object? This is called the Ship of Theseus dilemma and it has a "grandfather’s axe" variation. That is, if your grandfather left you his axe, but you eventually had to replace the handle because it broke and then replaced the head because it wore down... is it still your grandfather's axe?

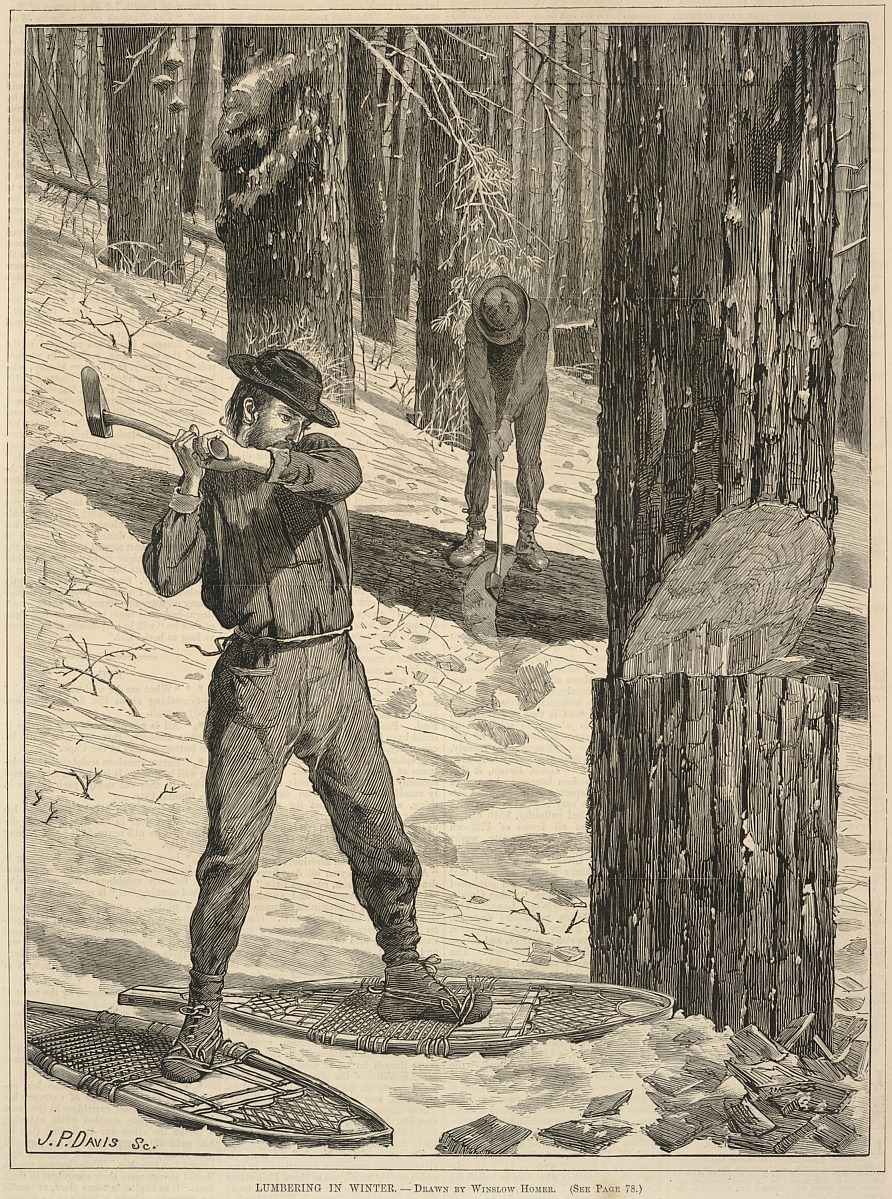

Lumbering in Winter, from Every Saturday: A Journal of Choice Reading, January 28, 1871. From the Smithsonian American Art Museum and its Renwick Gallery collection. See here. The Theseus Ship dilemma. Is your object still the same if every part of it has been replaced over time?

More things to think about...

-

Restoration generates money as objects are displayed or as they enter the commercial market. It is much easier to sell a good-looking object than a broken one.

-

Restoration gives less freedom to the public to interpret objects themselves. The more "accurate" an object is, the less room for interpretation it leaves.

-

Restoration can foster further investigation and research. Cleaning things off, investigating, researching necessary information before a restoration can lead to fantastic discoveries. Think about the paintings under the paintings.

-

Minimum intervention is about truth, keeping TRUE to the original. Why is the truth important? Does it really exist? Does it make people aware and proud of their past? Is that what gets visitors coming to the museum?

-

Is society just looking for stories, or does it care about truth? Do we prefer romance or beauty at the expense of "truth"?

-

Do we need professionals to filter information for us? On the other hand, minimum intervention may not be catering to the public. Conservation decisions can affect public viewing.

-

Truth is still important to some groups, how something really was. Are we taking away from their experience by restoring an object?

-

Do people find aged appearances more engaging or do they prefer things that look new?

-

What does society want? Who are we to give it to them? What does it believe? What is it interested in?

-

There are logical absurdities regarding the term “minimum intervention.” "Minimum" can ultimately be a subjective idea. Who decides? Is it up to the conservator, the curator, the museum director, the board of trustees, the donors, the general public?

-

If objects are just left alone (minimum intervention), they can get forgotten. They don’t exercise people’s curiosity. Does anybody care about the "ugly" stuff? Can we save the "ugly" stuff? Should we save items that society doesn't seem to care about? - Remember that everything costs money. Resources are not infinite. Budgets are mostly under-budgets.

Finally,

- Strangely enough, even a bad restoration can give an object a new life.

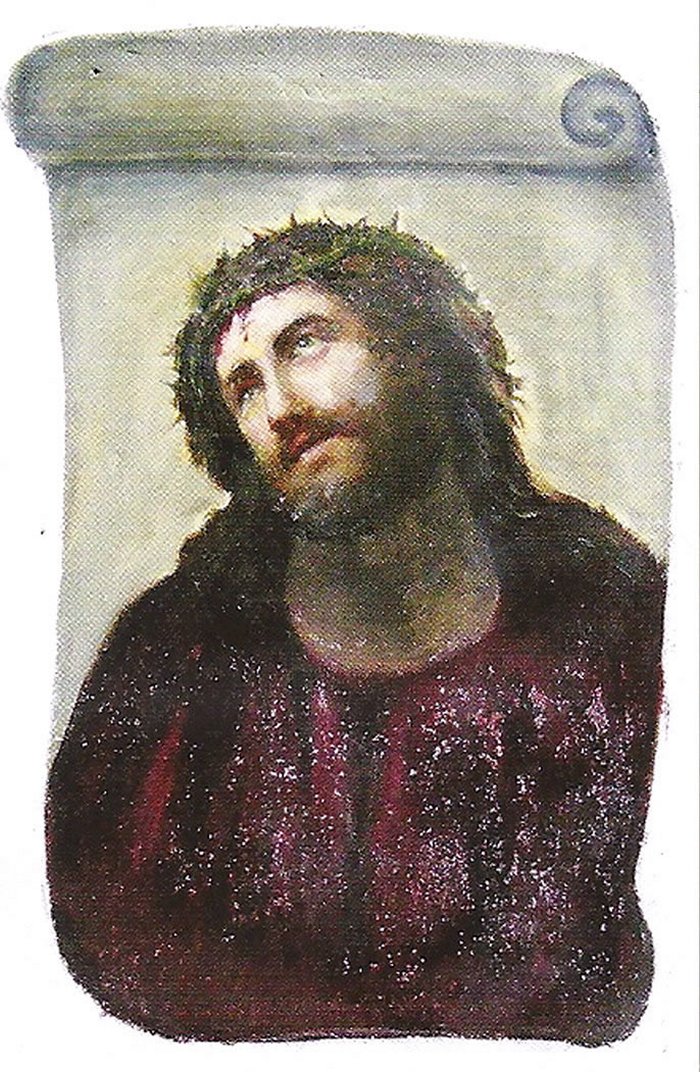

The Ecce Homo fresco by Elías García Martínez in the Sanctuary of Mercy church, Borja, Zaragoza, Spain before its infamous restoration in 2012. Image source: Wikipedia

You might remember this fresco. The bad restoration became a meme. Ecce Homo became Ecce Mono (Mono is Spanish for monkey). The best part about this new version of the fresco is that I can't even share the Wikipedia image of the restoration because "The restored fresco is assumed to be copyrighted by the artist, Cecilia Giménez, who is still living. According to Spanish law, it won't be public domain until 70 years after her death."

In other words, her restoration is now potentially considered an entirely new and independent work, with an artist author who holds copyrights over the piece. Not only that, but this sleepy little chapel in a random, small town in Spain suddenly saw a massive increase in tourism (and by extension, economic growth - much of which has been given to various charities). People came from all over just to see the bad restoration. They never cared about the original before. It seems to have been considered quite unremarkable. If a professional conservator-restorer had fixed this fresco, maybe nobody would have cared beyond the people who go to that particular church for services every week. So did 80-year-old Cecilia Giménez ultimately do this town a favour? Mind, this would be a very contentious idea to propose - imagine the dangers of having an army of people going out to intentionally deface art in order to attempt such a scheme.

Conclusions

I hope that this brief article has brought to light certain aspects of restoration and conservation ethics.

Objects in museum displays tend to look good. They have already gone through conservation processes. You should assume that every object on display has been checked and reviewed by a conservator before it went up. They are not what came out of the ground, or what was found. What you see has not only been curated, it has probably been conserved.

I am extremely interested in opening up the conversation to the general public because it is a fascinating topic. Conservation is, generally speaking, a very behind-the-scenes type of work. If you are interested in art, museums, history and material culture, knowing about conservation can bring a whole new aspect to interpretations which you may not have considered before. Follow me on Twitter and join me in this exciting project.