Montorsoli's restoration of the Laocoön's right arm was attached in an extended pose based on expectations, but when the real arm was found in excavations, it turns out it was bent at the elbow. Image source: Wikipedia.

"The conservator should endeavour only to use techniques and materials which, to the best of current knowledge, will not endanger the true nature of the object and which will not impede future treatment or the retrieval of information through scientific examination”

(Ashley-Smith, 1982:2)

The main issue in the debate between believing in an original, ‘true nature’ of an object and the reversibility principle is that if a conservator chooses a point in time for an object’s ‘original’ look and feel, all the cleaning that may occur based on this decision will effectively and irreversibly erase any evidence of any other aspects and interpretations of that object. The real question is: does it actually matter?

Definitions

Before beginning any analyses, working definitions are in order. The ‘true nature’ of an object “includes evidence of its origins, its original construction, the materials of which it is composed and information as to the technology used in its manufacture” (Caple 2000:62). The concept emphasizes the importance of the original object as a historic document, aesthetic entity and potential source of information (Caple 2000:141-143) and bases itself on a positivistic approach to knowledge where such a thing as one, single ‘truth’ is discoverable through scientific means. ‘True nature’ joins with the concepts of ‘authenticity’ and ‘integrity’ as “a measure of the wholeness and intactness of the natural and/or cultural heritage and its attributes” (Jokilehto 2009:81). This definition could lead a conservator to make the decision to irretrievably strip off many layers of later additions (whether natural or man-made) over the object in an attempt to reveal this ‘true’ meaning.

The concept of ‘reversibility’ began in the 1960s when conservators encountered the problems presented by past restoration work in the 19th and early 20th century that were difficult to remove and that caused objects more harm than good (Caple 2000:63). ‘Reversibility’ was meant to distinguish the modern, professional conservators from their ‘technician’ predecessors and emphasised the importance of not harming objects or hindering future treatments and investigations (ICON, article 9). As a concept, ‘reversibility’ displayed the interesting dichotomy of both insecurities in a profession where constant scientific discoveries can derail previous knowledge about what is ‘good’ overnight, and at the same time, the firm belief that constant scientific improvement meant that such a thing as ‘reversible’ treatments were completely possible – which in all reality, they are not (Caple 2000:64). ‘Reversibility’ implies that anything conservators do can be not just wrong, but very wrong – and that non-permanent treatments are paramount even if they mean risking the object to be subject to periodic retreatment – at its worst, 'reversibility’ almost hints at a lack of professional confidence and ability. Generally speaking, it would be more accurate to speak of ‘retreatability,’ but this is beyond the scope of this précis.

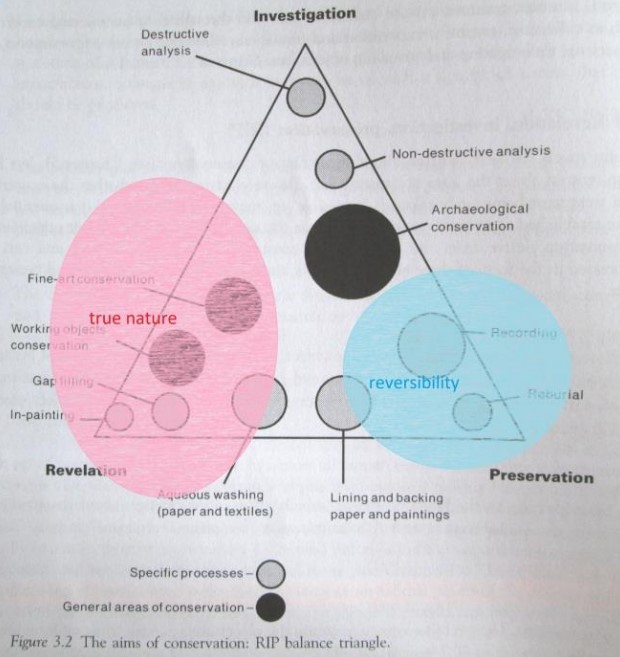

The rough location of the concepts of ‘true nature’ and ‘reversibility’ as presented in a RIP diagram of Revelation, Investigation and Preservation (Caple 2000:34). A particularly important thing to remember about the concept of ‘reversibility’ is that it is also dependent on the restorer’s skill (Ashley-Smith 1982:3).

The mythical Truth and the postmodern era

“It is impossible, as impossible as to raise the dead, to restore anything that has ever been great or beautiful in architecture.”

(Ruskin 1996:322)

It turned out, as time went by and ideas changed or were rediscovered (Brandi 1996), that the one Truth – with a capital ‘T’ – was so elusive when it came to object biographies that it almost didn’t exist – and it had to fall from use for professional, ethical guidelines. That idea of an authoritative, historical, accurate, single past with the (very real) power to shape present thoughts and decisions was not real, and by extension – the consequences of ignoring ‘reversibility’ loomed more threatening than before. If it was true, as Viollet-le-Duc posited, that “to restore…means neither to maintain… nor to repair… nor to rebuild… [but] to reestablish… in a finished state, which may in fact never have actually existed at any given time (Viollet-le-Duc 1996:314), then conservators were running the risks of re-writing history with the stroke of a brush (Richardson 1996:191).

It became important to start retaining old restorations due to historical meaning (Oddy 1994:5; ICOMOS 1964:article 11) and because of the capacity of objects to speak as ‘objective’ witnesses to the past (Caple 2006:206). It was realised that the most stringent cleaning would not necessarily leave an object with an ‘original’ surface (as that may have already been corroded away) (Caple 2006:207-208), and that “the attempt to reestablish ‘the original state’ was purely a mythical endeavour that could never be obtained; one could only have a ‘present state of the material’” (Carbonara 1996:237). Moreover, authors like Carbonara and France-Lanord argued that since whatever the ‘original’ was could not be brought back, that objects should be given back their “figurative context” by striking a balance between looking for the historical document and finding its aesthetic identity (Carbonara 1996:240; France-Lanord 1996:245; Caple 2000:141).

Not only were the dynamics of historical continuity acknowledged on objects, but documents such as the Nara Document on Authenticity of 1994 also highlighted cultural pluralism and respect for different viewpoints in the interpretation of object ‘truths’ (Jokilehto 2009:73; UNESCO) – a recognition that not all ‘truths’ are tangible and based on the materiality of the object, and more importantly, that depending on our backgrounds, we all see or fail to see very different ‘truths’ reflected in the object (Hassard 2008:158).

The importance of object interpretations

On the one hand, it is very significant that ideas on ‘true nature’ have evolved into today’s definitions. Interpretations of an object will help determine its conservation needs (Hall 2004:69), and the actions that are taken with ‘reversibility’ concepts in mind will shape both the tangible and intangible heritage contained in each object for future generations (Hassard 2008:150). Furthermore, objects that are displayed are the result of a conscious decision by the curators and conservators and show very specific points in their history – that is, they give out a false sense of ‘completeness’ as an object becomes isolated in time instead of being clearly presented as a snapshot of a continuum (Caple 2000:94-95).

All of the aforementioned points imply that as professionals, conservators have the qualifications and power to influence public thought and knowledge – and to a great extent, this is true. This may be partly the reason why single meanings rather than a multiplicity of them per object are presented – so as not to confuse. Still, whichever way in which we choose to display objects, in this view, we have now supposedly moved on to believing that the object has had (and will continue to have) a much longer life than us and therefore has more truths in it than we can see. It is no longer conservators and curators attempting to reveal and force the one truth that they inaccurately believed the object held, but the other way around. It is the object revealing its own truths while we do our best not to obscure them.

In Holtorf’s opinion, however, “cultural appreciation of the past is not now, and never has been, to any large extent dependent on original ancient sites and objects” (Holtorf 2011:289). Holtorf regards ancient objects and sites as the product of our interest in the past, and not the other way around (Holtorf 2011:289). His ideas “based on the truism that ‘every generation rewrites its history – and its history is the only history it has of the world’,” suggest that every time a new past is ‘created’ through our interpretations, we find objects and sites that become significant and supportive of our beliefs (Holtorf 2011:289). Thus, Holtorf goes beyond the concept of ‘true natures’ that are inherent to objects and sites, and instead argues that “archaeological heritage management should be concerned with actively and responsibly renewing the past in our time” (Holtorf 2011:294).

In other words, it is not the objects themselves that are important, but what we make of them. In a strange way, it seems to go back to the idea of a single meaning in objects that we ascribe to them – except this time, it has no unrealistic expectations of such a meaning coming from the object itself, but is acknowledged as directly springing from us: ‘true nature’ as a concept, here, is completely redundant – and ‘reversibility’, by extension, becomes a non-issue. It will be most interesting to observe, as time passes by, whether Holtorf’s ideas become the next step in conservation theory or whether we will go in another direction entirely.

I hope you liked this article. Do send me a message on Twitter and we can continue the conversation there!

Bibliography

Ashley‐Smith, J. (1982) The ethics of conservation, The Conservator, 6:1, p.1-5

Brandi, C (1996) Theory of Restoration I-III. In: Price, N. and Talley, M., et al. (1996) Historical and philosophical issues in the conservation of cultural heritage. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. p.230-235, 339-342, 377-379

Caple, C. (2000) Conservation skills. Judgement, method and decision making. London: Routledge.

Caple, C. (2006) Objects: Reluctant witnesses to the past. London: Routledge.

Carbonara, G (1996) The integration of the image: /problems in the restoration of monuments. In: Price, N. and Talley, M., et al. (1996) Historical and philosophical issues in the conservation of cultural heritage. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. p.236-243

France-Lanord, Albert. (1996) Knowing How to “Question” the Object before Restoring It. In: Price, N.S.; Talley Jr., M.K.; Melucco Vaccaro, A. Historical and Philosophical Issues in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage. Washington: The Getty Conservation Institute. p.244-247

Hall, A. (2004) A case study on the ethical considerations for an intervention upon a Tibetan religious sculpture, The Conservator, 28:1, 66-73

Hassard, F. (2009) Towards a new vision of restoration in the context of global change, Journal of the Institute of Conservation, 32:2, 149-163

Holtorf, C.J. (2011) Is the past a non-renewable resource? In: Layton, R. and Stone, P., et al. (2011) Destruction and conservation of cultural property. London: Routledge.

ICOMOS (1964) Venice charter. [online] Available at: http://www.icomos.org/charters/venice_e.pdf [Accessed: 17 May 2013].

The Institute of Conservation (2002) Professional Guidelines. [online] Available at: http://www.icon.org.uk/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=121&Itemid= [Accessed: 16 May 2013].

Jokilehto, J. (2009) Conservation principles in the international context. In: Richmond, A. and Bracker, A. (2009) Conservation. Principles, dilemmas and uncomfortable truths. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann. p.73-83

Oddy, A. (1994) Restoration – is it acceptable? In: Oddy, A. (1994) Restoration : is it acceptable?. [London]: British Museum Department of Conservation. p.3-8

Richardson, J. (1996) Crimes against the Cubists. In: Price, N. and Talley, M., et al. (1996) Historical and philosophical issues in the conservation of cultural heritage. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. p.185-192

Ruskin, J (1996) The lamp of memory, II. In: Price, N. and Talley, M., et al. (1996) Historical and philosophical issues in the conservation of cultural heritage. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. p.322-323

Viollet-le-Duc, E.E (1996) Restoration. In: Price, N. and Talley, M., et al. (1996) Historical and philosophical issues in the conservation of cultural heritage. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. p.314-318