Brief object description

Object number: DUROM 1967.40.a (vase) / DUROM 1967.40.b (lid)

Owner: University of Durham, Oriental Museum

Probable date: 19th-20th c.

Photo credits: Angelica Isa and Jeff Veitch

Image reproduction permission: University of Durham, Oriental Museum

Normally, it is possible to recognise and date chinese porcelains based on their colours, forms, motifs, styles and even maker's marks at the base.

Hard to read maker's mark similar to the character 隆, possible reference to Emperor Qianlong, giving an absolute minimal creation date of 1735.

However, this vase proved to be a challenge. The motifs, colours and shape could be identified independently through the history of chinese porcelain, but not in a manner consistent enough to be able to accurately date it to before the 20th century. The maker's mark was so unclear that it could be considered a garbled "fictitious" mark with no true meaning.

After a long period of research, it was concluded that based on the wuality of the glaze, the lack of consistency between colours and shapes, and the general style, this was probably a late piece, after the fall of the imperial ceramic factories of Ming and Qing, created as a souvenir of olden times and very possibly made for export for the chinese ex-pat populations in South East Asia between the mid 19th century and the 1930s.

State before conservation

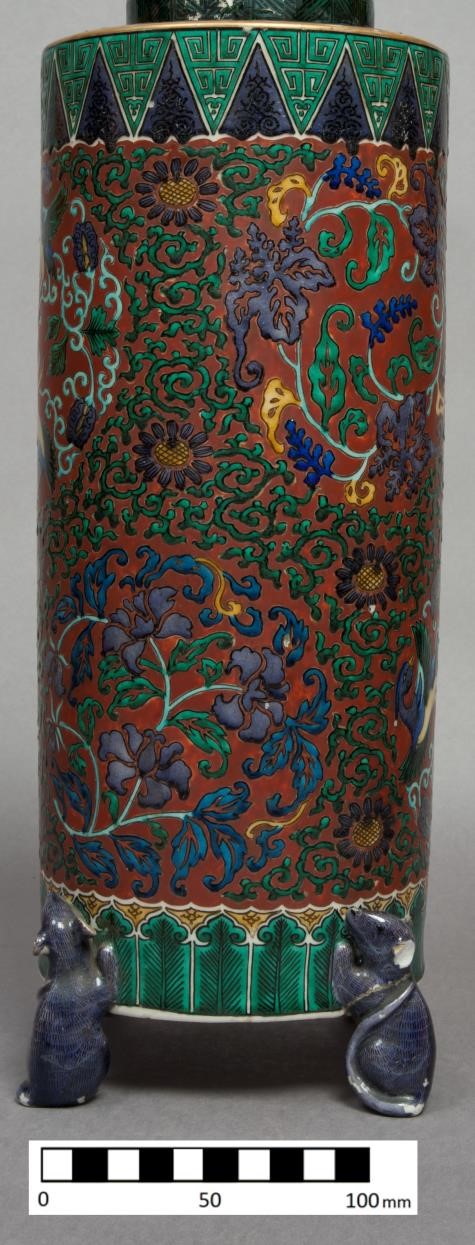

Photo of the vase body before conservation. Photo credit: Jeff Veitch

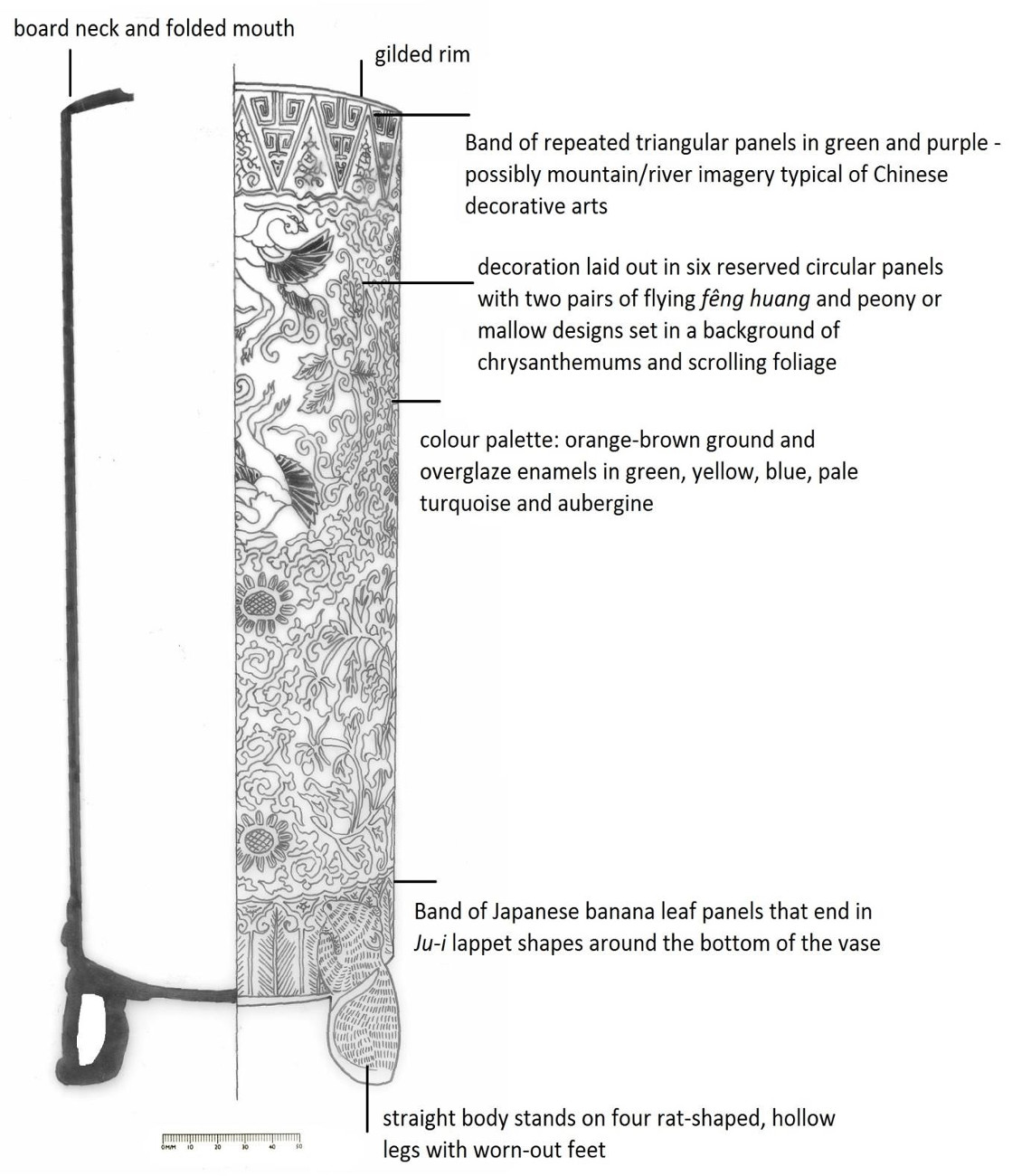

Techincal drawing for the main body.

This vase was an excellent research project where it was possible to see not only the damage caused by physical forces, but also the negative aesthetic qualities of old restorations on a glazed porcelain.

Lid of the vase. Rat holding grain. Notice the dull overpaints from old restorations and the loss in original glazing. Photo credit: Jeff Veitch

The interesting motif of the rat in Chinese iconography is different than that in the European. While the west may associate rats with sickness and pestilence (2020 ring any bells?), the rat is one of the 12 symbols of earth, associated with industry and properity thanks to the animal's great capacity to find and store large quantities of food.

Chinese mythology for the rat include stories of it creating the universe from a bite that separated the earth from the heavens and then stealing a bit of sunlight to provide us with light and energy, and giving people seeds to begin agriculture.

[The fêng-huang, a phoenix-like bird, is usually shown with] “the head of a pheasant and the beak of a swallow, a long flexible neck, plumage of many gorgeous colours, a flowing tail pointed backward as it flies.” (Hobson, 1976:293).

The idea of the fêng-huang is not of a single bird, but of a pair:

"fêng representing the male and huang representing the female; and as often as not the two are portrayed together." (Sowerby, 1940:21)

The orange colours and (male and female) phoenixes on the vase, apart from several plants (potential chrysanthemum, hibiscus, peony, mallow or irises) are references to the autumn, harvest, wealth and fertility.

Triangular “mountain patterns” show an arrangement of representations which would suggest mountains with rivers running in between their valleys. These upside down, zig-zag patterns “are typical of ancient space representations, in which distance is indicated by representing what is furthest away upside down” (Bulling, 1952:60). Moreover, the solid-looking, green is appropriate for solid mountains representing the earth while the swirly lines indicating motion (Bulling, 1952:70) in the purple-blue glaze may easily represent water.

Conservation process

The removal of the old infills and paint repairs on the lid was considered as a possible ethical issue since it meant taking away a chapter of the object’s history. However, not only were they unsightly, but due to the pulling action of the plaster and paint that had been used and the damage they had already caused to all the surrounding areas of original glaze, it was necessary to remove them for the purpose of protecting the original material from further detachment.

Additionally, the social meaning of the vessel theme in its Chinese context (described in previous sections) which emphasized prosperity, abundance, joviality, etc. made it clear that the aesthetic quality of the object should be improved – or else it would project an image contradictory to its original intention.

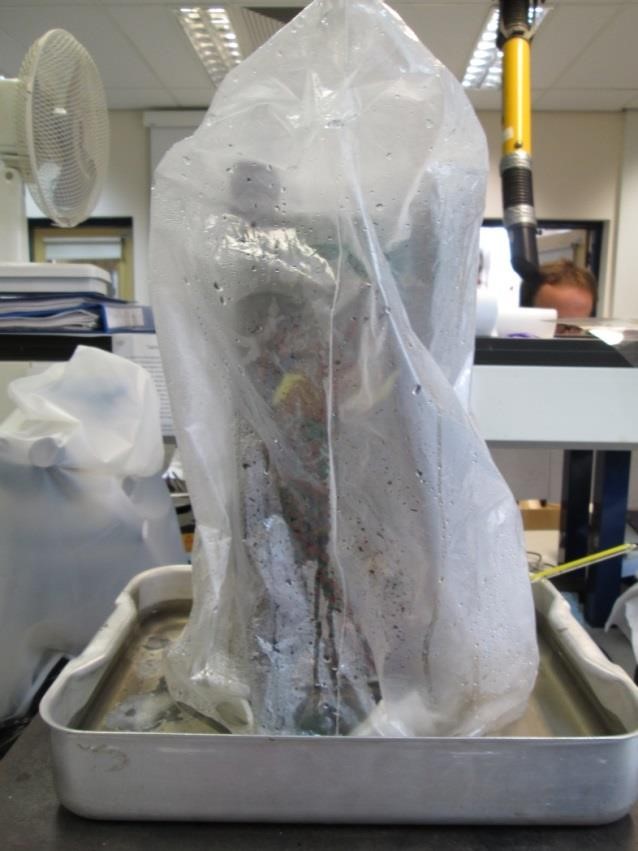

Embrittled animal glue holding together some of the rats on the feet of the vase and responsible for holding the weight of the object endangered its stability as it had dried and weakened over time.

To remove the old animal glue, the whole vase had to be steamed in a careful bath of hot water.

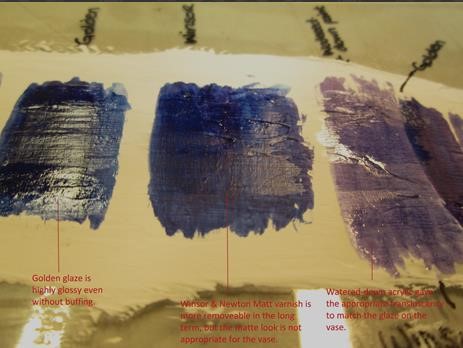

Old paint had to be mechanically removed with a scalpel under a microscope.

Different paints and glazes were tested separetely.

White plaster-based fills in preparation for re-painting old areas of missing glaze.

After conservation

Lid after restoration. Photo credit: Jeff Veitch.

Vase base after restoration. Photo credit: Jeff Veitch

Bibliography

Bulling, A. 1952. The meaning of China's most ancient art: An interpretation of pottery patterns from Kansu (Ma ch’ang and Pan-shan) and their development in the Shag, Chou and Han periods. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Hobson, R. 1976. Chinese pottery and porcelain An account of the potter’s art in China from primitive times to the present day. New York: Dover Publications.

Hobson, R. and Jenyns, S. 1954. Chinese Art: one hundred plates in colour reproducing pottery & porcelain of all periods, jades, paintings, lacquer, bronzes and furniture. 2nd ed. London: Ernest Benn Limited.

Sowerby, A. and Gibson, H. 1940. Nature in Chinese art. New York: The John Day Company.

Acknowledgments

This conservation process was carried out in 2013 with the generous guidance of Chris Caple (Durham University), Jennifer Jones (Durham University), Clare Hucklesby (Durham University), Richard Allen (Durham University), Jeff Veitch (Durham University), Helen Armstrong (Durham Oriental Museum), Ming Wilson (Victoria and Albert Museum) and Yu Ping Luk (British Museum).